Taking It to a New Level: The Urantia Book in Esperanto

Taking It to a New Level: The Urantia Book in Esperanto

By Jean Annet, Namur, Belgium, and Martin Benoit, Québec, Canada

“No evolutionary world can hope to progress beyond the first stage of settledness in light until it has achieved one language, one religion, and one philosophy. Being of one race greatly facilitates such achievement, but the many peoples of Urantia do not preclude the attainment of higher stages.” 55:3.22 (626.11)

As The Urantia Book has already been translated into more than 20 languages, the time is now ripe to translate it into Esperanto, the most important constructed language in our world. It is already one year since we received the approval of the Foundation to do so, and we have begun a gigantic task that will occupy us for years to come.

What is the Esperanto Language?

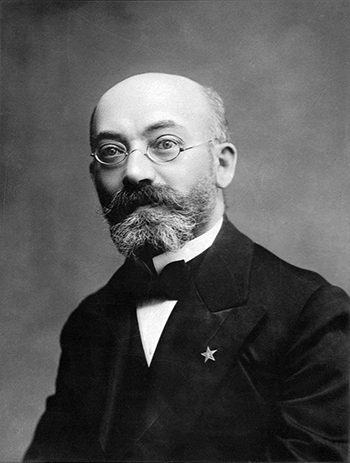

Esperanto is a constructed language, created in the 19th century by L. L. Zamenhof, an eye doctor in Poland, then part of the Russian Empire. When he was young, he experienced the pervasive animosity between the four peoples in Białystok where he lived: Russians, Poles, Jews, and Germans. Perceiving that it was mainly due to the language barrier, he decided to create an international language that would be used as a neutral language between all nations on Earth. His book was first published in 1887. The roots of Esperanto are heavily influenced by European languages, while its grammar—simple, regular, and expressive—is more akin to other language families. Esperanto grammar has been designed to be easy to learn, making the language about 10 times quicker to learn than other European languages.

One hundred thirty years later, the Esperanto movement encompasses tens of thousands of people in hundreds of Esperanto clubs in almost every nation on Earth. A culture of brotherhood between people and nations have developed, with yearly congresses, books, plays, music, and films. The World Esperanto Congress, an experience on its own, usually gathers between one and two thousand people from more than 70 countries every year. Activities range from scientific talks to cultural shows and guided tours of local attractions. They also include gatherings of diverse interest groups such as vegans, chess players, LGBTQ+, cat lovers, as well as many professional, political, and religious associations. The feeling of being able to efficiently communicate and understand everyone coming from everywhere with a comparable level of fluency is almost indescribable.

The Esperanto Translation

In the early 2000s, a Frenchman, JeanMarie Chaise, completed the translation of the entire Urantia Book into Esperanto. However, he died suddenly, and his translation sat on the shelves for years. But there were problems with his draft: It was modeled on the French translation and in need of much improvement. It not only needed revisions, but its terminology harmonized. More work would be needed to complete it.

At the start of 2020, a new international team was set up to participate in this colossal project. Let us now introduce the team:

Yves Nevelsteen, from Belgium, former president of the Flemish Esperanto Youth Association, initiated the Komputeko, a computer terminology within the framework of E@I (Esperanto on the Internet), and is active as an editor for the Esperanto Wikipedia.

• Lucas Perier, vice president of AFLLU (association for French-speaking readers), who has already revised 18 papers of the book.

• Anna Lobo de Carvalho from Brazil, who has already corrected several papers of the translation.

• Martin Benoit from Canada, who has corrected one paper of the book, has begun to create a glossary of neologisms of The Urantia Book, and has spoken Esperanto for almost 20 years.

• Jean Annet, from Belgium, former president of the Belgian Urantia Association, who directly received the translation of the book in Esperanto from JeanMarie Chaise.

Why Translate The Urantia Book into Esperanto?

One might ask: Why translate the book into Esperanto? What will it be used for and especially by whom? As we have seen, Esperanto was created by a Pole who wanted to foster human brotherhood. And since as a Jew he was a believer, he was convinced that if all men on Earth were brothers, they could only come from one Father and that would mean that there is only one God. Thus, within Esperanto there was an internal idea (la interna ideo ) of human brotherhood under the Fatherhood of God. If all Esperantists accept the idea of human fraternity, even if it is not the same for the Fatherhood of God, the interna ideo is implicit in the language and all Esperantists understand this. The Esperantist world is therefore an ideal target audience for transmitting the teachings of The Urantia Book.

Esperanto and The Urantia Book have many notable similarities to each other:

• They both started around the beginning of the 20th century.

• They do not belong to anyone, to any people, nation, association, or religion.

• They are disseminated by their “users.”

• They both have their opponents and their staunch supporters.

• They both organize national meetings and international congresses.

• They are both ahead of their time and will only take off in the future.

• It is difficult to determine numbers of followers for both. There are those who are absolutely convinced of it (who speak it, read it, study it). There are those who approach them from further away, and there are those who simply know of their existence

• And above all, they both carry the same message: the human brotherhood.

Rather than communicating the book to a nation in its own language, the Esperanto translation will be bringing it to a unique population at the global level, one which shares (within itself and with the revelation) the same ideal of human brotherhood. To have The Urantia Book in Esperanto will be to finally have the universal religion rendered in the universal language.

-700x360.png)

Number of Esperanto association members by country (2015)